Gainwell, a leader in healthcare cloud technology, is a project-based company that needs toreallocate staff quickly to support new contracts. In early 2022, filling a large number of open positions at Gainwell was a top priority.

“We really need to be able to staff positions quickly as we flex up and down,” said Julie Moore, Principal, Talent & Development. “If we’re working on a project for a state or client and that comes to an end, we need to be ready for the next one. Plus, we have a lot of priority roles, and with the right skills always in short supply, we can’t always fill them from the outside.”

Gainwell decided to accomplish this by fostering a culture centered around skills and internal mobility, and in parallel, improving recruitment and retention. SkyHive by Cornerstone powered Gainwell’s journey, from identifying the skills and capabilities of its workforce to reallocating and building the skills it needs to succeed.

Implementing Cornerstone Skills Transformation (formerly SkyHive Enterprise) meant learning the skills of the entire Gainwell workforce, and examining the skills needed in each role. From there, Gainwell could see the skills each employee needs to learn to bridge the gap between what they know and what they need to know to progress in their careers.

In March 2022, Gainwell launched Skills Transformation under the internal name of “G>Force.” The first, fundamental step was understanding what skills Gainwell employees had—not just what was listed on their current job description, but everything they had learned in their careers that might be useful and could be translated into the language of skills.

Gainwell, a leader in healthcare cloud technology, is a project-based company that needs toreallocate staff quickly to support new contracts. In early 2022, filling a large number of open positions at Gainwell was a top priority.

“We really need to be able to staff positions quickly as we flex up and down,” said Julie Moore, Principal, Talent & Development. “If we’re working on a project for a state or client and that comes to an end, we need to be ready for the next one. Plus, we have a lot of priority roles, and with the right skills always in short supply, we can’t always fill them from the outside.”

Gainwell decided to accomplish this by fostering a culture centered around skills and internal mobility, and in parallel, improving recruitment and retention. SkyHive by Cornerstone powered Gainwell’s journey, from identifying the skills and capabilities of its workforce to reallocating and building the skills it needs to succeed.

Implementing Cornerstone Skills Transformation (formerly SkyHive Enterprise) meant learning the skills of the entire Gainwell workforce, and examining the skills needed in each role. From there, Gainwell could see the skills each employee needs to learn to bridge the gap between what they know and what they need to know to progress in their careers.

In March 2022, Gainwell launched Skills Transformation under the internal name of “G>Force.” The first, fundamental step was understanding what skills Gainwell employees had—not just what was listed on their current job description, but everything they had learned in their careers that might be useful and could be translated into the language of skills.

Implementing the solution

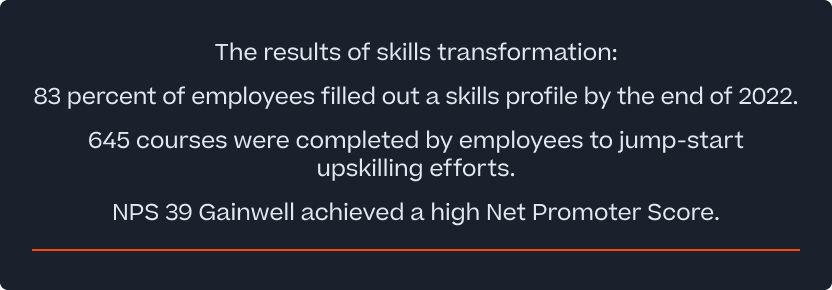

In the initial phase, Gainwell’s goal was for 80 percent of employees to complete a skills profile with at least 10 skills. The firm marketed G>Force internally using trainings, the company newsletter, and intranet. By July, it reached its goal: 10,600 employees (over 80 percent) completed a profile and identified, on average, 22 skills.

The number 22 is significant. Across the job market, individuals list an average of 11 skills when asked about their skillset. However, using SkyHive by Cornerstone, Gainwell employees discovered a broader range of skills, some of which they might not even have been aware they had. The Cornerstone Skills Transformation platform prompted employees about skills they might have based on their previous roles, experiences, and the contexts in which they gained those skills. For instance, the system could identify the skills a customer service manager had acquired over a 20-year career.

Completing profiles was only a first step in ensuring Gainwell’s employees get the most out of G>Force. “Our goal is to help us upskill our workforce and solve internal talent issues by creating more opportunities for internal mobility,” Moore says.

In July 2022, the company launched Skills Transformation’s training, career pathing, and mentoring modules. With these tools, employees can indicate their desired career path. Additionally, employees can find mentors, courses, projects, and new internal jobs all based on the skills they want and need to add.

Skills Transformation was integrated into SAP and is serving as a system of intelligence to Gainwell’s core HR system. Through SkyHive by Cornerstone’s automation of Gainwell’s talent architecture, the definitions of jobs and skills are being normalized across the HR function, ensuring consistency of skills identification for employees and jobs, clearly outlining skills of employees, skills matching to roles, the automation of skills gaps, and automating matching training to fill in those gaps.

“The business can finally move rapidly and with flexibility because we now know what our workforce is capable of accomplishing."

Julie Moore, Principal, Talent & Development, Gainwell

Outcomes & ROI

By the end of 2022, 83 percent of Gainwell employees had a skills profile. When employees complete training, projects, or earn a certification, they update their profiles with the new skills or added proficiency. Moore’s team is encouraging employees to review it quarterly or semiannually at a minimum.

Today, with G>Force, the company:

- Identifies internal employees to fill open positions and promote from within

- Improves recruiting and retention by providing a culture of growth, learning

- and opportunity.

- Uses employee expertise on critical projects by knowing who has what skills (e.g. cloud technology and agile methodologies)

The visibility into employee skills allows Gainwell to have greater workforce agility, shifting staff quickly between projects and winning new business. “Now we know things like ‘how many billable employees can I put on this project?’" Moore said. “Or, if we need to do an RFP—who has that expertise?"