Key Takeaways

- Skills are the new currency: Shift to 'skills-based organizations' essential for adapting to escalating global skills crisis in 2024.

- Companies moving to skill-focused hiring: Importance of skills is the sustainable competitive advantage, expertise crucial for future success.

- Skills taxonomy crucial: Classification system key to understanding, linking proficiency levels, and maintaining skill relationships for effective skilling experiences.

In business as in martial arts, skills are not an end, but a means to an end. Developing talent with the right skills, at the right time and place to deliver business goals is a challenge every organisation faces.

The challenge of hiring or developing talent with the skills needed by businesses is regularly cited as one of the top priorities of CEOs in all industries and sectors (McKinsey & Company, April 2023).

Despite tempting assumptions that the skills crisis was a by-product of the pandemic's great resignation, the challenge persists, especially in technology skills. This blog delves into the evidence from 2023, offering insights into the escalating global skills crisis. We explore the intersection of geopolitical uncertainties, technological advancements and the increasing demand for new skills. Leading businesses are adapting to become 'skills-based organizations' (SBO), redefining talent identification, hiring and promotion based on crucial skills rather than traditional qualifications. As we navigate this evolving landscape, the importance of skills in every aspect of business becomes evident, positioning them as the sustainable competitive advantage. This blog sets the stage for a series that demystifies the complexity surrounding skills, with the next installment focusing on how Cornerstone pioneers skilling in this dynamic environment.

Navigating the persistent skills crisis

You may be tempted to think that the skills crisis has passed and was just a function of the great resignment during the pandemic, but it remains a persistent, globally pervasive and growing challenge: one that is chronic in the arena of technology skills. Here is some of the evidence from 2023:

- In March 2023, a skills impact report by the Economist identified that 86 million workers in the Asia Pacific region need to be upskilled or reskilled with advanced digital skills to match the pace of technological change.

- In May 2023, a study by EY showed that technology skills permeate every industry and every job function.

- In May 2023, the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs report stated that of 803 employers surveyed 44% of workers’ skills will be disrupted in the next five years, particularly driven by AI (Artificial Intelligence).

- In August 2023, Politico reported that the European economies risk falling behind unless workers retrain in response to technological changes.

- In October 2023, the Australian Financial Review reported that ‘HR’s biggest trend is fixing the skills crisis’.

- In October 2023, The Institution of Engineering and Technology (The IET) stated that the skills gap in the engineering workforce threatened the UK’s ability to reach its net zero goals.

- In October 2023, Korn Ferry estimated talent shortages could cost the US economy $8.3 trillion by 2030.

- In November 2023, Thomson Reuters reported that the great resignation had removed 4.5 million people from the UK talent pool.

We live in a time of uncertainty driven by geopolitical tensions: the rise of authoritarian regimes; wars; climate change and mass migration, coincides with the increasing pace of technological change as the power of artificial intelligence becomes pervasive and available at scale to anyone. At the time of writing Sam Altman had just returned to Open AI and has promised that what awaits us in 2024 will make ChatGPT look like a quaint cousin.

The demand for new skills has only increased since the pandemic. In response to this challenge, leading businesses are transforming to become ‘skills-based organisations’ or SBO for short, that is an organisation where talent is identified, hired, developed, promoted based on the skills the business needs for now and the future, rather than academic qualifications, or experience in the same job family or industry.

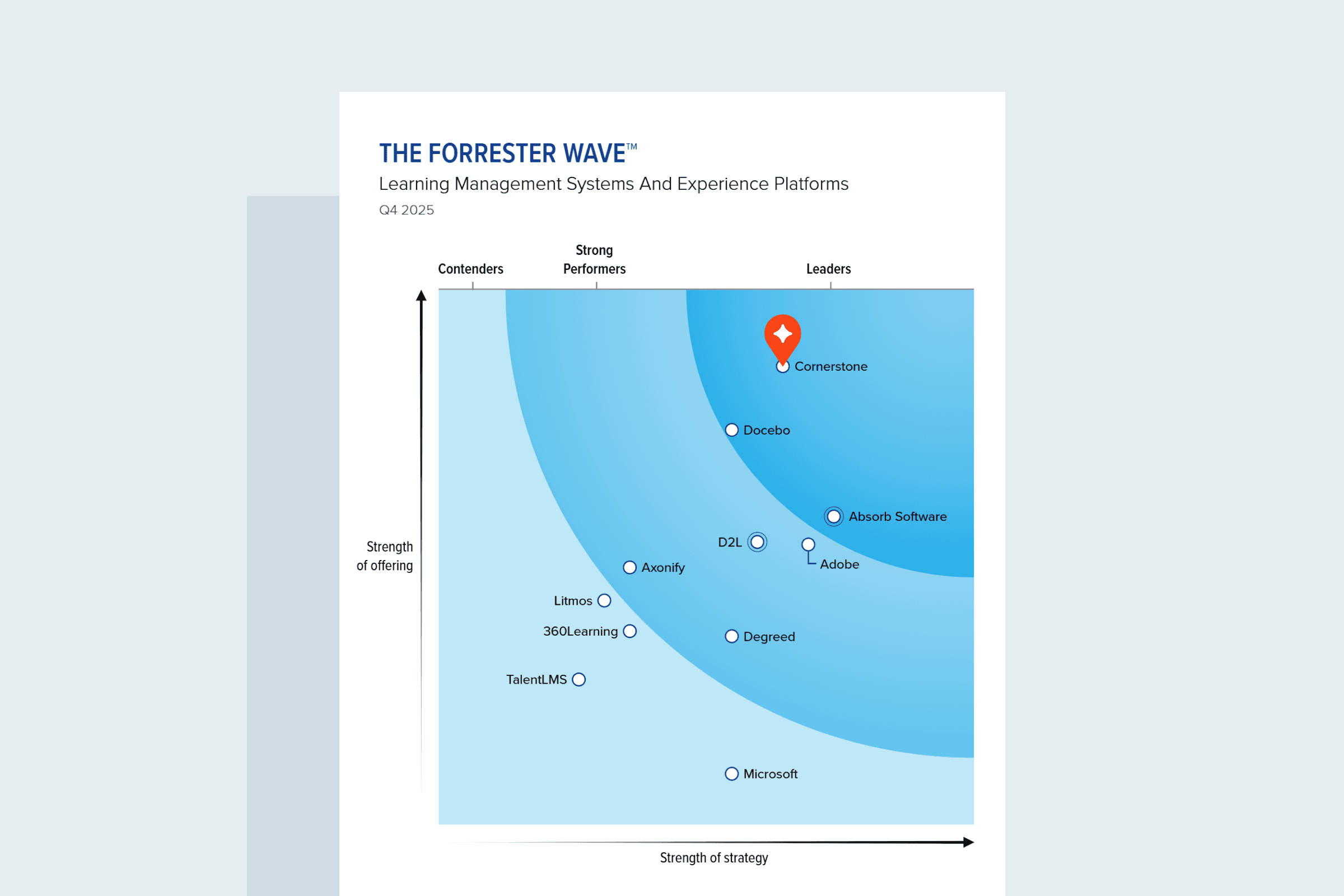

Because of this focus on skills, many learning technology providers have added skilling functionality to their product roadmaps, some, such as Cornerstone, are well ahead in the development of skilling functionality that is already delivering value to businesses.

Why are skills so important?

Skills touch everything, from talent acquisition to performance management, from competence assessment to learning recommendations, job architecture to talent sourcing, certification to digital credentials and so on. Every step, stage and function in the talent lifecycle is connected to skills and skilling, so much so that skills may be considered the common thread or currency of employment, enabling career vitality and career mobility.

Skills are also the only sustainable competitive advantage that any business can maintain in the long run, every other resource that a business needs will eventually be extracted, designed, manufactured, developed, reproduced, packaged, delivered and maintained cheaper and faster by a competitor.

In business there are no leisure learners, all learning is done with a purpose in mind, either one that supports a business need or enables career progression (ideally both) through skills development.

Before we go further, what exactly are Skills?

This may seem like a question with an obvious answer, but the business world has diluted the educationalist’s definition of skills. An educational purist might say that skills are something that a person can do; they are either cognitive (e.g., divide one number by another) or psychomotor (e.g., drive a car). Some skills are micro (walking), some are mesa (hiking) some are meta (expedition planning), but they can all be expressed as a verb, and you may remember from your schooling that ‘a verb is a doing word’. In the sentence ‘Celine developed a new software programme using the Python programming language on her MacBook Pro’, the skill is that of developing software.

However, the business world has extended, or muddied that definition to include methodologies (e.g., AGILE), languages (e.g. Python), products (e.g. Microsoft Office), standards (e.g. 5G), broad subject domains (e.g., Data Science) or abstract and nebulous concepts (e.g., Emotional Intelligence, Cyber Hygiene). The battle for a pure definition of skills is over, and contemporary skills taxonomies are often full of things that are not skills.

We should waste no time focusing on whether we are meeting the perfect definition of skills in business sooner is better than perfect; any skills model (taxonomy or ontology) that delivers measurable progress toward business goals is good enough!

What is a skills taxonomy?

A taxonomy is simply a classification system, often but not always hierarchical. Most skills taxonomies are alphabetical lists of skills nodes (single skills), sometimes with the addition of synonyms for the skill (software development and software programming), associated acronyms (AGILE), and occasionally brief descriptions. A skills taxonomy may be linked to a job architecture taxonomy of job roles grouped into job families. The defining characteristic of a skills taxonomy is that it is one-dimensional.

What is a skills ontology?

If a skills taxonomy is a list, an ontology is a dynamic mesh, in which the relationship between skills is defined and maintained. An ontology shows the relationship between skills, for example, public speaking is a skill related to, but different from lecturing, which in turn is related to lesson planning. Ontologies also contextualise skills to job roles, job families and industries. Programming skills are found in job roles, in the engineering job family in the software industry (and other industries). The defining characteristic of a skills ontology is that it is multi-dimensional.

How are proficiency levels defined?

Skills may exist at multiple levels of proficiency from lower to higher levels but there is no standard, de facto or otherwise, for naming or meaning of proficiency levels. One organisation’s beginner may be another’s novice, or foundational level; furthermore, not all learning content providers align their content to a proficiency level model, so mapping skills to content at proficiency levels is always subjective.

What is a skills architecture?

A skills architecture is an overarching design for how skills data and functionality are connected and operate to deliver a consistent and coherent skilling experience to the user. A well-designed skills architecture such as used throughout the Cornerstone TXP should adopt three principles:

- Be Open: That is provide a means for interoperability with other systems that use skills data, typically through a suite of public, documented APIs (Application Programming Interfaces).

- Be Agnostic: That allows any number and variety of skills taxonomies or ontologies to be used and unified into a single model.

- Be Flexible: That is allow any element of the chosen skills taxonomies or ontologies to be modified (add, change, delete, renamed), hidden or revealed from view to the user.

Many learning and skilling technology platforms do not provide an open, agnostic, and flexible skills architecture, thereby locking the client in to an environment that does not play well with other systems that use skilling data.

In summary, our exploration has spotlighted the central role of skills in contemporary business. The evidence from 2023 solidifies the ongoing challenges, particularly in the tech sector. The evolution towards 'skills-based organisations' reflects a strategic response, underlining skills as a key driver in talent management. From talent acquisition to performance management, skills are the linchpin constituting a sustainable competitive advantage.

This article is the first in a series of skills-focused blogs designed to unravel the complexity, terminology and uncertainty that persists in the market around skills. Next in the series we will look at how Cornerstone brings skilling to life in its Talent Experience Platform (TXP).